Artist Oleksandr Klymenko: “I’m happy because I feel like a person who participates in the real transformation of death into life”

On Apr. 16, 2019, an exhibition of icons by Kyivan artists Sofia Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko, “Passiones/Passion,” was opened in Kyiv’s St. Sophia Cathedral. The new series of Icons on Ammo Boxes as part of their joint initiative with the PFVMH, “Buy and Icon – Save a Life,” was painted in commemoration of those killed in the Russian-Ukrainian war. According to the authors, the exhibition is dedicated to the fifth anniversary of the official beginning of the war in Donbas, of which date this year symbolically coincides with the beginning of Holy Week.

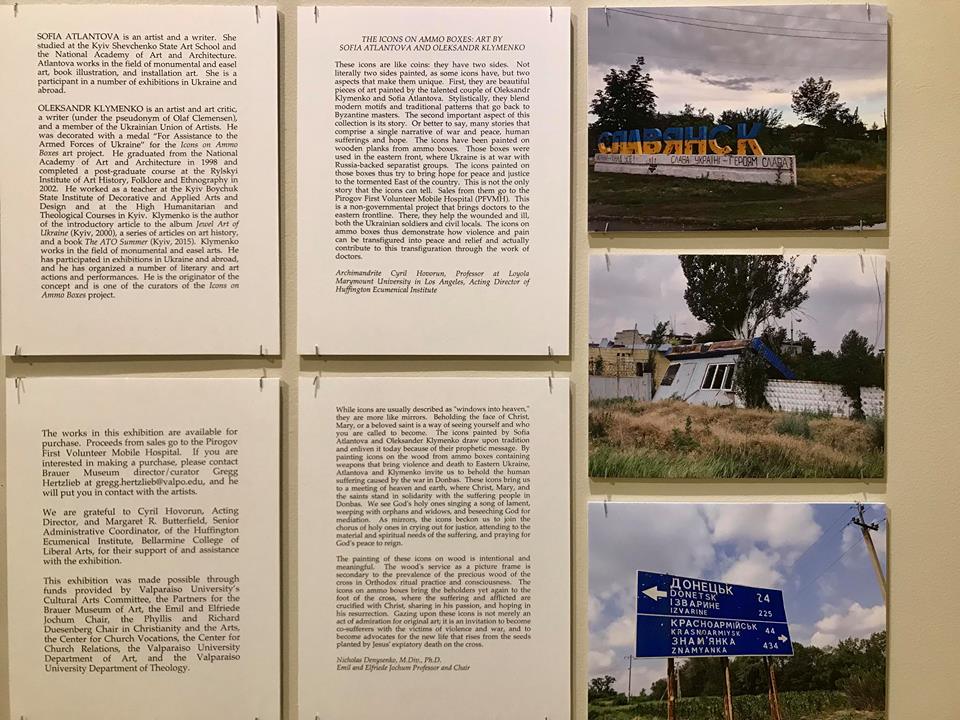

“Passiones/Passion” is by far not the first exhibition of Icons on Ammo Boxes brought from the combat zone. The icons by Sofia Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko were exhibited in many cities in Ukraine, Europe (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Romania), the United States, and Canada, as well as during a number of international events.

The main idea of the art project is the transformation of death (symbolized by ammo boxes) into life (traditionally symbolized by icons in Ukrainian culture). The receipts from the icons sale go the Pirogov First Volunteer Mobile Hospital to support activities of its volunteer medics. In this way, this victory of life over death happens not only on the figurative and symbolic level but also in reality: the artists have already donated to the PFVMH more than UAH 5 million over four years of their collaboration with the mobile hospital, becoming its main sponsors.

In late February 2019, after returning from a voyage to the United States, Oleksandr Klymenko gave an interview, telling about how the idea of the project came up, how exhibitions beyond the seas are held, how the icons sell and who buys them, and a lot more.

“With the PFVMH, the concept of my project gained perfection”

How did this idea of painting icons on ammo boxes come up? To whom did it occur first?

Me. In the fall of 2014, I, Sofia and several other artists organized an exhibition in support of the Main Military Clinical Hospital of Ukraine. It was also an exhibition of icons, but conventional icons. During the exhibition, a few icons were sold (not mine). At the time, the Parliamentary election campaign was in progress, and many candidates visited the exhibition. One of them bought a whole little stack of icons for his relatives and the Sich battalion. He invited me and another artist to the battalion’s base to hand the icons. There, I saw piles of AKM ammo boxes and note that the board of one of the boxes looked very much like the boards on which we painted icons.

I asked the servicemen about what they did with those boxes. They said that they used them to make benches or tables or simply burnt them in stoves as firewood. Then I asked to give me one box, and painted on it the first icon – “Holy Mother with the Child”. This icon looked like it was from a museum, because the board was dusty, darkened, very old, and the icon’s stylistics was of the beautiful ancient Byzantine Empire. It was then that I got the idea of a conceptual art project in which the theme of war could be combined with what was not connected with the war at all. The collision of things, an antinomy. That is, I was interested in this antinomicity, when you combine the uncombinable, an ammo box board and an icon, with an incredibly organic result. You paint an icon, and then you have an impression that it’s been there for a thousand years.

I asked the servicemen about what they did with those boxes. They said that they used them to make benches or tables or simply burnt them in stoves as firewood. Then I asked to give me one box, and painted on it the first icon – “Holy Mother with the Child”. This icon looked like it was from a museum, because the board was dusty, darkened, very old, and the icon’s stylistics was of the beautiful ancient Byzantine Empire. It was then that I got the idea of a conceptual art project in which the theme of war could be combined with what was not connected with the war at all. The collision of things, an antinomy. That is, I was interested in this antinomicity, when you combine the uncombinable, an ammo box board and an icon, with an incredibly organic result. You paint an icon, and then you have an impression that it’s been there for a thousand years.

So the main idea of this project is the transformation of death into life, both being antinomic things as well. I invited two more artists, Sofia Atlantova and Natalia Volobuyeva. We carried out a pilot exhibition – wanted to see how the audience would respond. And the project was officially launched in St. Sophia of Kyiv four years ago, in February 2015.

Was it decided at once to give the receipts from selling the icons to the voluntary hospital?

Almost at once – as soon as my icons started selling, because I saw that this project had the potential for volunteering. In addition, let’s say I had been already involved in the financing of the PFVMH at the time as an “intermediary”. This is a good story, and apparently, not everybody knows its details.

Almost at once – as soon as my icons started selling, because I saw that this project had the potential for volunteering. In addition, let’s say I had been already involved in the financing of the PFVMH at the time as an “intermediary”. This is a good story, and apparently, not everybody knows its details.

In November 2014, a monk of one of Kyiv’s monasteries, an acquaintance of mine, called me and said, “Oleksandr, I heard that you were fundraising for the hospital. I’ve got money for you.” I went to him, and he handed me a bagful of money – UAH 100,000. He said this bag was given to him by some stranger who asked to give the money over to those who suffered from this war, who needed help most badly.

I said I’d give it a thought. The Main Military Hospital at the time had no problems with supplies. So could there be any projects that are not too well known but essential? On my Facebook timeline, I came across a post by Gennadiy Druzenko, who desperately asked to help pay for a vehicle for the PFVMH. I thought: “A cool idea – a volunteer hospital!” I was also impressed by the sincerity of his call for help. I knew Gennadiy a little since we had many mutual acquaintances, and I also met with him several times before and during the Maidan revolution. Still, I made some inquiries among people who knew him well and whom I trusted, and heard only commendations. I ascertained that he was a person who did not steal that money, that the PFVMH project was a humanitarian and important for Ukraine, and that it would work systematically. Then I called Gennadiy and said there was money for him. He said: “You know, we are now praying, because tomorrow we have to pick up the vehicle but lack UAH 70,000. If we fail to pay up, we’ll lose it.”

We met, Gennadiy told me about his hospital in detail, and I realized that I had not mistaken. The vehicle bought for this money was called “Angel”. The hospital was launched and I felt like a witness to a miracle. Miracles like that might have been witnessed by Kyiv Pechersk monks a thousand years ago if any.

We met, Gennadiy told me about his hospital in detail, and I realized that I had not mistaken. The vehicle bought for this money was called “Angel”. The hospital was launched and I felt like a witness to a miracle. Miracles like that might have been witnessed by Kyiv Pechersk monks a thousand years ago if any.

Then I saw how efficiently the PFVMH worked at the front, so I did not hesitate on whom the money for sold icons should be given. It is because money should work in systemic projects where they think strategically.

And then the concept of my project gained perfection: the transformation of life into death not only symbolically but really. Now I’m awfully happy because I feel like a person involved in a real transformation of death into life, in a real fight against death.

“Next to the icons were portraits of the Heavenly Hundred heroes. It was as if they were blending with each other, taking the event up to a certain metaphysical level”

The last time I wrote about your exhibition was on January 11 this year, when Icons on Ammo Boxes were presented during IOTA Inaugural Conference in Iasi, Romania. What icon shows were there after that?

Back in Kyiv from Romania, we had just a few hours to take a shower, collect works, and set off for the United States.

In January, the first exhibition was at Indiana University Bloomington. We presented there our project on the campus. From Bloomington, we moved to Valparaiso University, also in Indiana. It is one of the most powerful Protestant universities in America, which also has, as I see it, one of the best museums in the area, the Brauer Museum of Art. It was this museum where we presented our project. Concurrently with Valparaiso, icons were also exhibited in Chicago.

In January, the first exhibition was at Indiana University Bloomington. We presented there our project on the campus. From Bloomington, we moved to Valparaiso University, also in Indiana. It is one of the most powerful Protestant universities in America, which also has, as I see it, one of the best museums in the area, the Brauer Museum of Art. It was this museum where we presented our project. Concurrently with Valparaiso, icons were also exhibited in Chicago.

In February, we flew over the ocean again. The first exhibition was held in Chicago, in the Sts. Peter & Paul Parish of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA, the Constantinople Patriarchate. The two following exhibitions took place in the cathedrals of St. Andrew the First-Called, in South Bound Brook, NJ, and Silver Spring, a Washington suburb in Maryland.

South Bound Brook is in essence “Jerusalem of the Orthodox Ukrainians of America.” There is a cemetery where leading figures of Ukrainian culture rest, a consistory, and a seminary of the UOC of the USA. Our exhibition coincided in time with events that took place there in commemoration of the Heavenly Hundred, and thus became part of these events, which included a visit of President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko to South Bound Brook.

Who accompanied you on these tours of the United States?

The three traveled in January: me, Sofia Atlantova, who is the other participant in our art project and my wife, as well as Gennady Druzenko, a co-founder and Supervisory Board Chairman of the PFVMH. In February, I was accompanied only by Gennadiy.

The three traveled in January: me, Sofia Atlantova, who is the other participant in our art project and my wife, as well as Gennady Druzenko, a co-founder and Supervisory Board Chairman of the PFVMH. In February, I was accompanied only by Gennadiy.

How does it happen in general? You do not come somewhere with your icons and say, “We’ll have an exhibition here,” do you?

Many people from different parts of North America ask to organize expositions of our icons in their places. Therefore, we have divided our “exhibition activities”: a part of our icons travel through the United States, and another part, without me, through Canada. In Canada, we began the year before last. Since then, the exhibition has been moving from the west of the country – Alberta – eastward, and now it is hosted by the Cardinal Josyf Slipyi Ukrainian Museum in Montreal. In the United States, we started with Los Angeles in California last April.

Our project is now quite well known among the Ukrainian Diaspora in America and the university professoriate. They write and invite me from various universities.

Speaking of our trips this year, we were invited by Prof. David C. Williams of the Indiana University’s Center for Constitutional Democracy, who visited Ukraine last October and even went to see how the PFVMH worked in Eastern Ukraine; Deacon Nicholas Denysenko, world-renowned theologian of Ukrainian origin; Gregg Hertzlieb, director/curator of the Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University; the community of the Sts. Peter & Paul Parish in Chicago; and Archbishop Daniel of the UOC of the USA, who became interested in our project earlier, when he was an exarch of the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew in Ukraine during the Council.

Speaking of our trips this year, we were invited by Prof. David C. Williams of the Indiana University’s Center for Constitutional Democracy, who visited Ukraine last October and even went to see how the PFVMH worked in Eastern Ukraine; Deacon Nicholas Denysenko, world-renowned theologian of Ukrainian origin; Gregg Hertzlieb, director/curator of the Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University; the community of the Sts. Peter & Paul Parish in Chicago; and Archbishop Daniel of the UOC of the USA, who became interested in our project earlier, when he was an exarch of the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew in Ukraine during the Council.

We sincerely thank them, the leadership of both universities, and all those who got involved in this cause for the invitation and organization of the exhibitions.

How do you carry your icons over the ocean?

It depends. We send them by mail or take along. This year, we took a part of them with us to the airplane, and the other part had been brought to America last year when we held the exhibition in Los Angeles.

До літака ікони берете як багаж?Do you take the icons as luggage?

До літака ікони берете як багаж?Do you take the icons as luggage?

Yes, as luggage.

But it’s very heavy luggage!

Yes, but we carry it nevertheless. Sometimes you have to pay for it. When we went to LA, the airline’s computer hung, so they let us board free of charge.

How many icons are traveling through the United States?

About 50.

Is their number gradually dropping because some are bought?

We replenish the collection from time to time. Although you are right, now there are fewer icons there.

Are there any problems with the Ministry of Culture and the Customs?

The MinCult documents our icons; otherwise they wouldn’t have been released. And customs officials in Boryspil say that they know and support our art project. They always gladly greet us, kindly let us through, and generally assist in every way. One can say they are one of the project’s partners because I have not seen at any other customs office such a level of respect and favor for the project as in Boryspil. I did not expect enthusiasm like that among our customs officers – art experts.

Do you insure your icons?

In America, exhibition organizers sometimes do. At Valparaiso University, the icons were insured. There, at the Brauer Museum of Art, everything was organized wonderfully, because professional curators worked there – they made an impeccable exhibition, organized to the best standards of curatorial art.

In America, exhibition organizers sometimes do. At Valparaiso University, the icons were insured. There, at the Brauer Museum of Art, everything was organized wonderfully, because professional curators worked there – they made an impeccable exhibition, organized to the best standards of curatorial art.

However, everything was done very well in other places too. In South Bound Brook, portraits of the Heavenly Hundred heroes were next to the icons. It was as if they were blending with each other, taking the event up to a certain metaphysical level.

“America has a very sincere and democratic atmosphere. We felt respect for what I and my wife did and for work of PFVMH doctors”

Who else were the speakers at the openings of exhibitions besides you and Gennadiy Druzenko?

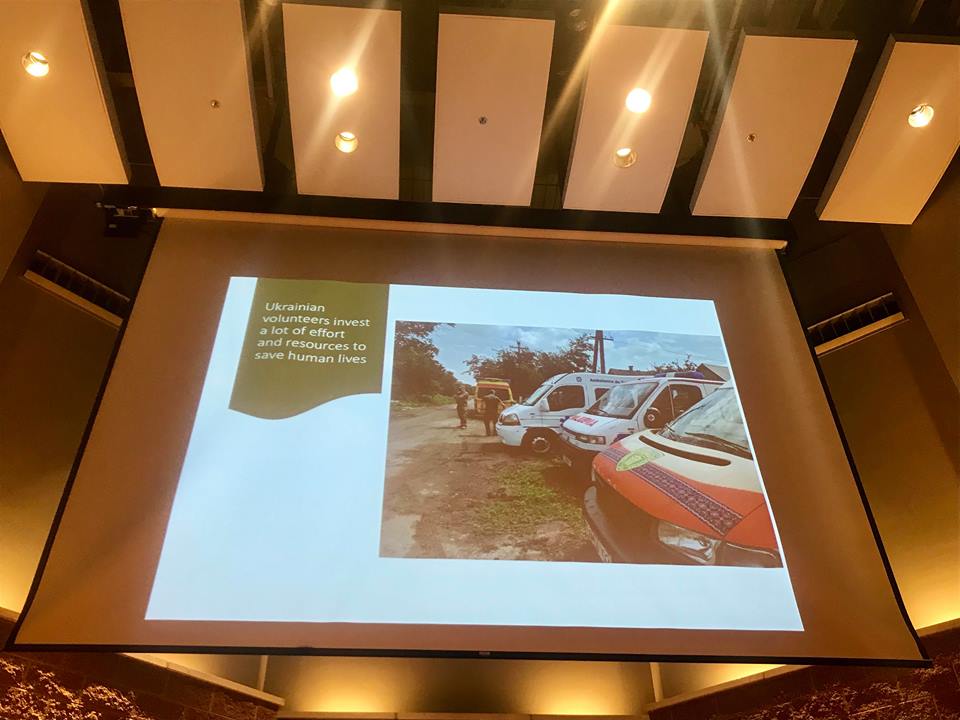

Archimandrite Cyril (Hovorun), Professor at the Loyola Marymount University and a member of the PFVMH Board of Trustees, participated in the opening of one of these exhibitions. He came to Valparaiso and read a lecture on the war in Donbas, as well as reported about his visit to Donbas with Gennadiy Druzenko last summer. Parsons of the communities spoke. I’m also grateful to Metropolitan Anthony (Scherba), the First Hierarch of the UOC of the USA – he attended the opening of our exhibition in South Bound Brook. There were other people who spoke and supported. We had many fruitful discussions and conversations.

Archimandrite Cyril (Hovorun), Professor at the Loyola Marymount University and a member of the PFVMH Board of Trustees, participated in the opening of one of these exhibitions. He came to Valparaiso and read a lecture on the war in Donbas, as well as reported about his visit to Donbas with Gennadiy Druzenko last summer. Parsons of the communities spoke. I’m also grateful to Metropolitan Anthony (Scherba), the First Hierarch of the UOC of the USA – he attended the opening of our exhibition in South Bound Brook. There were other people who spoke and supported. We had many fruitful discussions and conversations.

In America, in general, there is a very sincere and democratic atmosphere. At the same time, we felt respect for both what I and my wife did, that is, the art project, and for the work of PFVMH doctors.

What did you and Gennady talk about at the openings?

In speeches like that, I usually reveal the conceptual aspects of our project – what we have written about more than once – with some minor variations. For example, at Valparaiso University, I and Fr. Nicholas Denysenko read a very serious lecture for students, where the first part was about the theological concept of Orthodox Church icon, and the second, how our project correlated with this concept. It looks, never before had I a theological presentation so complex and conceptually loaded. In fact, we sorted out all the theological nuances of our art project.

Are there many visitors coming to see the icons? Who are they?

Yes, many. In fact, we had a full house at some of the presentations.

Yes, many. In fact, we had a full house at some of the presentations.

The audience includes Americans of Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian origin, both specially invited guests and people who are just interested. Everyone treats our project with the same respect.

Certainly, it cannot be said that our project there addresses only the Ukrainian Diaspora. As it turned out, Americans are interested in what is happening in Ukraine, and this project gives them an opportunity to learn more about the current war. Because in fact, for a serious thoughtful American, it is clear that there are a few places where the destiny of the world, its future, is determined today, and Ukraine is one of those places. At least many of them think so. I also maintain this opinion.

Would you call the audience who came to the exhibitions “average Americans”?

Different people come. The university intellectual elite among them. On the other hand, for example, there was such a guy who came to one of our exhibitions: all over covered with tattoos, in a baseball cap, hands in pockets, chewing gum bubbles. He came, bought the most expensive icon, and just left.

And what about buyers – can they be called very well off?

The public that buy the icons is diverse, too. For example, I learned from the organizers that one of our icons was bought as a present for the Vice President of the United States. Among the buyers, there was one of the laser inventors; now he is of a very respectable age.

The public that buy the icons is diverse, too. For example, I learned from the organizers that one of our icons was bought as a present for the Vice President of the United States. Among the buyers, there was one of the laser inventors; now he is of a very respectable age.

In America, it’s difficult to answer such a question. Everybody dresses quite modestly there. Nobody is accompanied by guards. Nobody will tell you how many millions he has. For example, I happened to speak with a buyer of an icon, and then I was told that he was one of America’s leading collectors, whose collection included works by Andy Warhol. And there are other people, who ask to sell them works on installments.

That is, telling a rich from a poor in America is difficult. I did not encounter there anything the way it is in Ukraine when an oligarch comes along with five guards.

What interested the visitors of the exhibitions you spoke with?

This project is interesting in that it works, in particular, in the secular space. The communication was very active. I talked to many people. Sometimes, they were interested in quite unexpected things, for example, if relations between Ukrainians and Russians are similar to the relations between the white and the black Americans in the 20th century? How much would Martin Luther King be relevant in Ukraine? Of course, everybody asked about the PFVMH, when the war would end, how long I paint an icon, or if we would stand if Putin went on a full-scale war on us – the latter worries everybody. They asked if we paint our icons in blindages under fire, how often I visit Donbas. These are standard questions. But they also asked, for example, whether I liked their local cuisine.

There are people who are aware of the situation in Ukraine, but there are those who know almost nothing about it. That is, they have heard something, know about Putin. The exhibitions allowed them to learn the truth. When they hear that children and old people suffer, it immediately makes the project important and interesting for them. With all their ability to make money, there is a willingness to help in America. For this nation, serving society, helping another person, as far as I’ve got it, is an important thing. It’s like the reverse side of their rationality.

There are people who are aware of the situation in Ukraine, but there are those who know almost nothing about it. That is, they have heard something, know about Putin. The exhibitions allowed them to learn the truth. When they hear that children and old people suffer, it immediately makes the project important and interesting for them. With all their ability to make money, there is a willingness to help in America. For this nation, serving society, helping another person, as far as I’ve got it, is an important thing. It’s like the reverse side of their rationality.

May these icons hang in a Catholic temple?

Of course, they may. And they do – in Orthodox and Catholic and Greek Catholic churches. These icons fit perfectly into the space of art galleries of museums and exhibition centers. Our project also works great as a contemporary art project, clear and interesting to secular people who are far from Christianity. Many people buy these works for the sake of their artistic qualities. Others perceive them purely as icons, the concept of which clearly continues the theological traditions of Christian art: the transformation of death into life. Indeed, the victory of life over death is the leitmotif of Christianity: the cross, which was a symbol of death, became the symbol of the Resurrection. Similarly, when an ammo box board turns into an icon, it continues this tradition.

For contemporary art, I would say, the conceptual component of this project is what makes it interesting and brings it closer to the art of metamodernism. That is, at first glance, the project is postmodern to a certain extent because very often it contains the quotationality and a combination of the uncombinable. But here, there is no game component, and the pathos of the project, I would say, is modernist – a real transformation of the world. Just this in our project interests people who are far from Christianity. In addition, the theme of volunteering, the theme of helping the hospital by the means of art, is important and interesting for any decent person.

“Universities, in my opinion, is where Ukraine definitely loses to America. I dream of Ukrainian Princeton and Harvard”

Did you sell many icons during the exhibitions?

Yes, about 25 works. The last trip was the most successful of all. It brought good results in terms of both money and awareness since many people came to the exhibitions.

Yes, about 25 works. The last trip was the most successful of all. It brought good results in terms of both money and awareness since many people came to the exhibitions.

Who paid for air tickets, accommodation, and meals?

Accommodation and meals were covered by the organizers of the exhibitions. We only bought tickets and paid for the rent of the car in which we traveled in January because there were many locations. In February, we were driven by volunteers or priests of the UOC of the USA: New York – South Bound Brook – Princeton – Washington – New York.

When you were driving, did you violate the road regulations? Did you have to pay fines?

We did not violate the regulations but had an accident. It was my fourth traffic accident over my 20-year driving experience and the second one through my fault. I’ve just got used to a manual transmission and forgot that the car had an automatic gearbox. So, on entering the priority road, I habitually tried to use that automatic box lever as a shifter to go from the second to the third gear to accelerate. As a result, our car stopped abruptly, and we were “caught up” by the car that was behind us on the priority road.

How did this accident end?

In fact, I got an unforgettable impression. The policeman arrived very quickly. The first question was: are all alive, not injured? After that, he went to the other car to make sure that all were safe and unharmed there, too. Then he returned to me, asked about details of the accident, and wrote everything down to his notebook; went again to the other driver and recorded his testimony. Finally, he gave us his business cards and was gone. That is, the whole accident registration business took about five minutes.

And then?

And then we went our own way each. The car was insured, so now, perhaps, insurance companies are dealing with each other. I really liked it in America, because I expected that the accident registration would take some two or three hours – with tape measures, unnecessary comments by police, and such other things to which we’ve got accustomed in Ukraine. And that policeman “swept like a wind”. Didn’t measure anything. Maybe, he took a photo – I didn’t notice. I did not lie to him, just explained everything. It seems he understood because he had no more questions.

My understanding is that people who meet with an accident there try to explain what has happened as honestly as possible. It’s more advantageous to do like that because if you lie and it’s brought to light, you won’t like the consequences.

Were there any particularly pleasant or interesting meetings during the exhibitions in the United States?

For me, the meetings with representatives of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of America and representatives of the Ukrainian Diaspora were the most pleasant. For example, I cannot forget the communication with Deacon Nicholas Denysenko, which was just a revelation to me. There was an incredible meeting with Gayle Woloschak, Professor of Radiation Oncology and Radiology at the Northwestern University in Chicago and President of the American Orthodox Theological Society. She is one of the leading Orthodox theologians and one of the world’s leading microbiologists who study cancer. And of course the unforgettable meeting with Archbishop Daniel. He acted as our partner and promoter in America and did it very successfully.

For me, the meetings with representatives of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of America and representatives of the Ukrainian Diaspora were the most pleasant. For example, I cannot forget the communication with Deacon Nicholas Denysenko, which was just a revelation to me. There was an incredible meeting with Gayle Woloschak, Professor of Radiation Oncology and Radiology at the Northwestern University in Chicago and President of the American Orthodox Theological Society. She is one of the leading Orthodox theologians and one of the world’s leading microbiologists who study cancer. And of course the unforgettable meeting with Archbishop Daniel. He acted as our partner and promoter in America and did it very successfully.

I like the democracy of the Ukrainian communities there in general. In my opinion, without this experience of our Diaspora, simply getting Tomos and creating the structure of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine will be wrong. I’m talking about the financial transparency, respect of the senior for the younger, the ability of all to cooperate with everyone from the bottom up to bishops, the democratic behavior of the episcopate that we lack in Ukraine, the openness and sincerity of these people.

After several trips to the USA, what is your impression of America and Americans?

America is very varied, and its diversity is impressive.

Perhaps my biggest impression is of the American universities. Coming back to our politics, what is difficult to escape, I have not seen the slogan among our presidential candidates for which I would fully support the candidate: let’s make campuses of Ukrainian universities like those in America. Or at least let’s make it our 10-year goal.

That is, universities, in my opinion, is where Ukraine definitely loses to America. I’ve been at many of them with an exhibition, visited some of them just for the sake of it, and lectured in many, and I dream of Ukrainian Princeton and Harvard.

You and Sofia gave the hospital many thousands of dollars. Does the thought come to you: OK, that’s enough, I need to earn a bit for myself?

No. My main idea is, let this war end sooner.

I like feeling needed. That’s it.

As soon as the war ends, the project is over. Would you want its last icon to be painted on the remnants of trophy boxes of Russian weaponry?

I’d be happy. I would generally want the whole project to be painted only on Russian boxes – of weapons that killed Ukrainian soldiers. But actually, all of them are Soviet-made. The youngest box I’ve come across was from 1987, and the oldest, from 1943.

Both you and Sofia are not only artists but also writers. Do you have time for literature? Are you writing anything new now?

Not for the last six months. I’ve practically no free minute. But, in principle, I devote all the free time left after this project to literature. I had a free month last fall and worked on a big novel about the relationship between people in Ukrainian society against the background of the war and decommunization, a novel following the traditions of Ukrainian chimeric prose. And, by the way, if someone does not know: I write under the pseudonym of Olaf Clemensen.

Oleksandr Zheleznyak